Celebrity Scandal: The Story of the John Lennon Concert Piano

Pianos rarely create scandals, much less, make headlines in The New York Times, The New York Daily News, and People magazine. However, the Lennon-Ono-Green-Warhol Baldwin 1929 Model D 9’ Ebony Concert Grand is no ordinary piano. Not only is it among the last of the Baldwins crafted during the Golden Age of piano making, but it was owned, gifted, and displayed by icons in the late 20th-century art world–John Lennon, Yoko Ono, Sam Green, and Andy Warhol.

And yet, astonishingly, it disappeared.

The disappearance of the piano from the New York Academy Art was a scandal that dominated the headlines of New York and the national press in May of 2000. Particularly distraught, Samuel Adams Green (scion of the Founding Father Samuel Adams), art collector, curator, and promoter of pop art, emphasized the value of the piano–given its rarity and the impressive list of people who interacted with it.

The disappearance of the piano from the New York Academy Art was a scandal that dominated the headlines of New York and the national press in May of 2000. Particularly distraught, Samuel Adams Green (scion of the Founding Father Samuel Adams), art collector, curator, and promoter of pop art, emphasized the value of the piano–given its rarity and the impressive list of people who interacted with it.

In a letter to Bruce Ferguson in 1999, Sam Green wrote, “Actually, no one but (John Lennon) and I knew how valuable and unique this piano was. It could be compared to a Stradivarius violin. It was the last of an advanced technology to be used in American pianos before the crash of 1929. I arranged for friends of mine to donate another grand to the Academy because of the eventuality that I would be placing my Lennon piano elsewhere.”

Clearly, the piano wasn’t meant to be on loan, not a gift, and certainly not intended to be sold to someone else. However, not only had the piano apparently been sold, but it had simply disappeared.

By 2000, neither Sam Green nor the New York Academy of Art knew where the Lennon-Ono-Green-Warhol piano was. In fact, Green realized it was missing only when he was contacted by a dealer in California who offered to sell it back to him for $80,000 to $100,000. It turned out that the offer was a fake and the California dealer didn’t have the piano, but it was enough to tip Green off that the piano was no longer at the Academy.

A co-founder of the Academy, Green was reluctant to tarnish its reputation with a lawsuit. However, litigation seemed necessary if only to generate enough media interest so the new owner of the piano would identify themselves.

A co-founder of the Academy, Green was reluctant to tarnish its reputation with a lawsuit. However, litigation seemed necessary if only to generate enough media interest so the new owner of the piano would identify themselves.

Fast forward to 2022. Karen Lile and Kendall Ross Bean of Piano Finders, a California-based company that, among other projects, appraised Elton John’s legendary red pianos, were contacted by Mercersburg Academy to appraise an unusual piano.

On the Baldwin nine-foot grand piano was a tarnished brass plate that said “For Sam Love From Yoko and John 1979.” The artifact was famously missing until it was eventually tracked down to an auctioneer in Arab, Alabama, Buddy Bain, who put it on display in the lobby of a local bank.

Authenticating the piano was a Herculean task for Bean and Lile, especially since the documents related to the piano listed the wrong serial number, and there were very few papers available. Since the guitar company Gibson had purchased Baldwin, many records were lost. Lile spent 200 hours in libraries poring over documents to piece together the story of this unique piano for provenance after Kendall gave the piano a thorough inspection to validate its authenticity.

According to Lile and Bean’s findings, the piano was constructed in 1929 and was located in a building where radio shows were broadcast. Nothing is known of the piano’s owners or history from 1929 to 1978 when John Lennon purchased it from the Baldwin retail store at 58th and 7th Avenue. However, Bean believes that the piano was re-strung and re-hammered before John Lennon bought it.

In 1978, John Lennon was just beginning to re-emerge after his lengthy focus on family life. In 1979, John and Yoko gifted the piano to Sam Green, but the piano would continue to provide Lennon with creative inspiration, and Sam Green recounts the role the piano played in his final compositions.

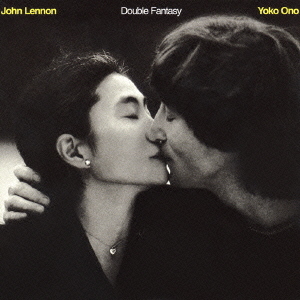

In court papers from Sam Green’s eventual lawsuit, he stated, “They (Lennon and Ono) would often visit and stay in my house in Fire Island. Yoko thought the creative atmosphere would help inspire John to write songs for their new album.” This turned out to be John Lennon’s final album, Double Fantasy, which earned him a posthumous Grammy.

In court papers from Sam Green’s eventual lawsuit, he stated, “They (Lennon and Ono) would often visit and stay in my house in Fire Island. Yoko thought the creative atmosphere would help inspire John to write songs for their new album.” This turned out to be John Lennon’s final album, Double Fantasy, which earned him a posthumous Grammy.

The couple sought refuge from the paparazzi on Fire Island. Lile, an expert on boating as well as pianos, admits it would not have been easy to transport the piano over water, and Bean points out some rust on the strings and the tuning pins show the effects of humidity on Fire Island. Since Sam Green’s cottage wasn’t temperature-controlled, the wood on the pin block most likely swelled and contracted. This may be a factor in Sam Green’s decision to eventually move the piano from Fire Island to its new home in Andy Warhol’s Interview office between 1983 and 1986.

Sam Green and Warhol had been close for 25 years by that time, and the art curator was a frequent visitor of The Factory and part of Warhol’s inner circle. The piano became a fixture in the office of Interview magazine, located inside Warhol’s sprawling T-shaped building that extended from 32nd to 33rd street with a wing connecting to Madison Avenue.

After Warhol’s death, Sam Green lent the piano to the New York Academy of Art, where the mystery of the missing piano began. At this point, Lile and Bean had traced the history of the piano backward and forwards from the scandal–but there was one missing piece of the puzzle–how did the piano get lost before it ended up with Buddy Bain and who sold it?

The reason for this suppressed history is that, naturally, the person who sold the piano didn’t want to be embroiled in a scandal. After a lengthy interview with Buddy Bain, Lile, and Bean finally discovered that the person who was listed as merely transporting the piano, Harold Katz, had, in fact, sold it to Buddy Bain.

According to court documents, Sam Green said, “It’s a sad loss–the disappearance of the piano from the New York Academy of Art. I’d lent it to the school during the formative years, hoping that having it there would give the students and faculty a feeling of being connected to the Arts.” However, somewhere along the way, this vehicle of inspiration ended up in a basement and moved with other pianos the Academy wanted to dispose of. Harold Katz offered to do the job at a discounted bulk fee.

Katz realized what he had in his possession and had sold, although he was understandably unwilling to discuss the matter for 23 years, given the heat of the scandal at the time. In an interview with Lile, Katz said, “How would you feel if you had a Picasso in your possession and sold it for $300 not knowing what you had.”

As the mystery is solved, the piano’s Odyssey remains as compelling as ever and another reason to own a cultural artifact that has inspired musical compositions, scandal, and curiosity for nearly a century.